The Chosen Man

and why he was chosen.

The story-line for The Chosen Man emerged while I was watching a television news about mortgage loan scandals. I saw a connection to the get-rich-quick ethos behind the 17th century Dutch financial bubble known as ‘tulip mania’. A few days later I heard that just one person was responsible for a major French banking scandal, and the plot began to thicken.

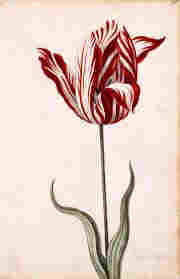

The Chosen Man centres on tulip mania, the first recorded financial bubble. At its height in the early spring of 1637, a Dutch merchant paid 6,650 guilders for a dozen tulip bulbs. At that time 300 guilders would have kept an entire family for a whole year. The merchant wasn’t a wealthy man buying wildly expensive bulbs to plant and enjoy for their colour; he intended to sell on and make a profit. Records document instances of farmers exchanging their land for bulbs, and men exchanging their homes to acquire a single rare bulb. Artisans sold their tools to ‘invest’ in tulips. Between 1635 and 1637 everyone, it seemed, fell prey to this collective madness – why?

During the 1630s there was a brief ice-age in northern Europe. Having lived in Holland, I can fully appreciate why tulips – introduced into northern Europe at the turn of the 17th century – became so popular. Tulips bring colour and a promise of spring at the end of long, dark, tedious winters. The 1630s was also the Dutch ‘golden age’. The Protestant work ethic meant people now had a disposable income, which they spent on house-building and home-improvements, and investing in works of art. But the bubonic plague was everywhere: death was on every doorstep. Many feared they might not have time to enjoy their wealth and took to the thrill and risk of gambling.

This was happening during an intense period of political intrigue in Europe. Spain had lost its Dutch provinces and was engaged in a protracted war to regain them. Cardinal Richelieu in France had signed a treaty with the Dutch, and was involved in ‘arrangements’ with the Vatican to hinder Spain in Flanders. French ships raided the Spanish fleet supplying its men. The Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand had vowed to impose Catholicism throughout his empire before his death and was harrying the Spanish king to win the fight in Flanders. Statesmen throughout Europe were angling for power and control, and then, suddenly, apparently spontaneously, there is a financial bubble in Holland bringing ruin to the people who financed resistance to the Habsburgs.

I filed these connections away in my mind until sometime later, while visiting the British National Trust property Cotehele in Cornwall, it all came together in an unexpected manner. I saw the portrait of a 17th century Lady Edgcombe, a face with no trace of humour or forgiveness. Here was the mean mother-in-law for my new heroine, Alina, daughter of an impoverished Spanish grandee, and the one woman who does not entirely fall prey to Ludo’s charm. But while this bit is pure fiction, the events and conditions of Alina’s life are based on the contemporary circumstances and conditions of her rank and gender.

After that visit, I began investigate how the Vatican had been playing a double game with Spain and Emperor Ferdinand: Pope Urban VIII wanted to limit Habsburg power, not bolster it. Cardinal Richelieu was also involved in this. The conspiracy would have needed an agent provocateur, though. Someone they could subsequently eliminate. Unless the chosen man was sharp enough to play his own game.

My fictional Ludo da Portovenere is a multi-lingual Genoese ‘rich trade’ merchant with no visible loyalties. Ludo sets his own terms and conditions, and is wise enough to know he’ll have to escape before powerful men need to erase all trace of his actions. As his name suggests, Ludo sees it as a game. A profitable game. He has no obligations to anyone, except perhaps Alina, but she has to decide whether Ludo is her chosen man.

Copyright © A.M.Arredondo. All Rights Reserved.